As a boy, Blas Omar Jaime spent many afternoons studying about his ancestors. Over yerba mate and torta fritas, his mom, Ederlinda Miguelina Yelón, handed alongside the information she had saved in Chaná, a throaty language spoken by barely shifting the lips or tongue.

The Chaná are an Indigenous folks in Argentina and Uruguay whose lives had been intertwined with the mighty Paraná River, the second longest in South America. They revered silence, thought of birds their guardians and sang their infants lullabies: Utalá tapey-’é, uá utalá dioi — sleep baby, the solar has gone to sleep.

Ms. Miguelina Yelón urged her son to guard their tales by conserving them secret. So it was not till many years later, not too long ago retired and looking for out folks with whom he may chat, that he made a startling discovery: Nobody else appeared to talk Chaná. Students had lengthy thought of the language extinct.

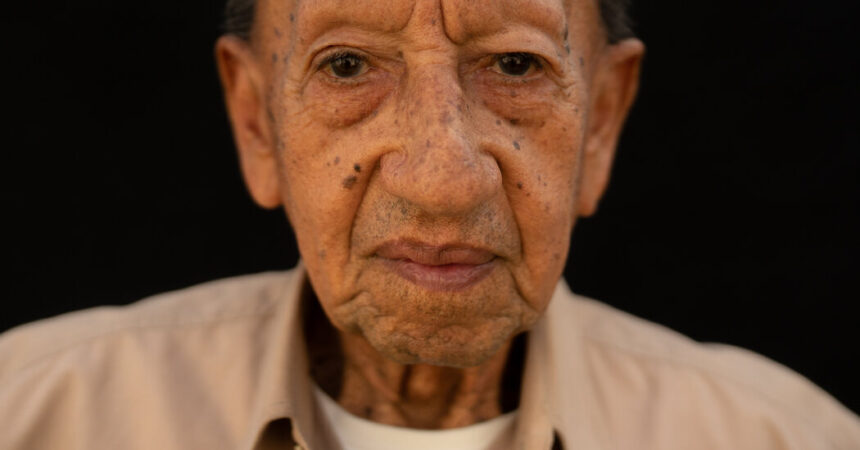

“I mentioned: ‘I exist. I’m right here,’” mentioned Mr. Jaime, now 89, sitting in his sparse kitchen on the outskirts of Paraná, a midsize metropolis within the Argentine province of Entre Ríos.

These phrases kicked off a journey for Mr. Jaime, who has spent practically 20 years resurrecting Chaná and, in some ways, putting the Indigenous group again on the map. For UNESCO, whose mission contains the preservation of languages, he is a vital vault of data.

His painstaking work with a linguist has produced a dictionary of roughly 1,000 Chaná phrases. For folks of Indigenous ancestry in Argentina, he’s a beacon that has impressed many to attach with their historical past. And for Argentina, he’s a part of an necessary, if nonetheless fraught, reckoning over its historical past of colonization and Indigenous erasure.

“Language is what provides you identification,” Mr. Jaime mentioned. “If somebody doesn’t have their language, they’re not a folks.”

Alongside the way in which, Mr. Jaime has had brushes of movie star. The topic of a number of documentaries, he has delivered a TED Speak, lent his face and voice to a espresso model and has appeared in an academic cartoon in regards to the Chaná. Final 12 months, a recording of him talking Chaná echoed throughout downtown Buenos Aires as a part of an artist venture that sought to honor Argentina’s Indigenous historical past.

Now, a passing of the guard is underway, to his daughter Evangelina Jaime, who has discovered Chaná from her father and is educating it to others. (What number of Chaná stay in Argentina is unclear.)

“It’s generations and generations of silence,” mentioned Ms. Jaime, 46. “However we gained’t be silent anymore.”

Archaeologists hint the presence of Chaná folks again roughly 2,000 years in what’s now the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Entre Rios, in addition to elements of present-day Uruguay. The primary European document of the Chaná was made within the sixteenth century by Spanish explorers.

They fished, lived a nomadic life and had been expert clay artisans. With colonization, the Chaná had been displaced, their territory shrunk and their numbers dwindled as they assimilated into newly established Argentina, which launched army campaigns to eradicate Indigenous communities and open land for settlement.

Earlier than Mr. Jaime revealed his information of Chaná, the final identified document of the language was in 1815, when Dámaso A. Larrañaga, a priest, met three older Chaná males in Uruguay and documented what he discovered in regards to the language in two notebooks. Solely a kind of books survived, containing 70 phrases.

The trove of data that Mr. Jaime obtained from his mom was way more expansive. Ms. Miguelina Yelón was an adá oyendén — a “lady reminiscence keeper” — somebody who historically preserved the group’s information.

In line with Mr. Jaime, solely girls had been Chaná reminiscence keepers.

“This was a matriarchy,” mentioned Ms. Jaime. “Ladies had been those who guided the Chaná folks. However one thing occurred — we’re unsure what — that made males take management once more. And ladies agreed to cede that energy in alternate for them being the one guardians of that historical past.”

Ms. Miguelina Yelón didn’t have any daughters to whom she may cross alongside her information. (Her three daughters all died as youngsters.) So she turned to Mr. Jaime.

That’s how he got here to spend his afternoons absorbing tales of the Chaná, studying phrases that described their world: “atamá” means “river”; “vanatí beáda” is “tree”; “tijuinem” means “god”; “yogüin” is “fireplace.”

His mom warned him to not share what he knew with anybody. “From the time we had been born, we hid our tradition, as a result of in these days, you had been discriminated in opposition to for being aboriginal,” he mentioned.

A long time handed. Mr. Jaime led a diverse life, working as a supply boy, in a publishing home, as a touring jewellery salesman, in a authorities transportation division, as a cabdriver and as a Mormon preacher. When he was 71 and retired, he was invited to an Indigenous occasion, and was nudged out into the gang to inform his story.

Since then, Mr. Jaime has not stopped speaking.

One of many first to publicize him was Daniel Tirso Fiorotto, a journalist who labored for La Nación, a nationwide newspaper.

“I knew that this was a treasure,” mentioned Mr. Fiorotto, who tracked Mr. Jaime down and revealed his first story in March 2005. “I left there amazed.”

After studying Mr. Fiorotto’s article, Pedro Viegas Barros, a linguist, additionally met with Mr. Jaime and located a person who clearly had fragments of a language, even when it had eroded with the shortage of use.

The assembly marked the beginning of a yearslong collaboration. Mr. Viegas Barros wrote a number of papers on the method of attempting to recuperate the language, and he and Mr. Jaime revealed a dictionary that included legends and Chaná rituals.

In line with UNESCO, no less than 40 % of the world’s languages — or greater than 2,600 — had been underneath risk of disappearing in 2016 as a result of they had been spoken by a comparatively small variety of folks, the most recent 12 months for which dependable knowledge is offered.

Referring to Mr. Jaime, Serena Heckler, a program specialist on the UNESCO regional workplace in Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, mentioned, “We’re very conscious of the significance of what he’s doing.”

Whereas his work preserving Chaná shouldn’t be the one case of a language as soon as thought lifeless abruptly reappearing, it’s exceptionally uncommon, Ms. Heckler mentioned.

In Argentina, as in different international locations within the Americas, Indigenous folks endured systemic repression that contributed to the erosion or disappearance of their languages. In some circumstances, youngsters had been crushed in class for talking a language aside from Spanish, Ms. Heckler mentioned.

Salvaging a language as uncommon as Chaná is tough, she added.

“Individuals should be dedicated to creating it a part of their identification,” Ms. Heckler mentioned. “These are utterly totally different grammatical constructions, and new methods of considering.”

That problem resonates with Ms. Jaime, who has needed to overcome entrenched beliefs among the many Chaná.

“It was handed down from era to era: Don’t cry. Don’t present your self. Don’t snigger too loudly. Converse quietly. Don’t say something to anybody,” she mentioned.

For a time, that’s how Ms. Jaime additionally lived.

She shunned her ancestry as a youngster as a result of she was bullied at college and scolded by academics who doubted her when she mentioned she was Chaná.

After her father began talking publicly, she helped him arrange language courses he supplied at a neighborhood museum.

Within the course of, she started studying the language. Now she teaches Chaná on-line to college students world wide — many are teachers, although some say they’ve traces of Indigenous ancestry, with a small quantity believing they might be descendants of Chaná.

She plans to show the language to her grown son so he can proceed their household’s work.

Again at Mr. Jaime’s kitchen desk, the older man wrote his title out within the language he’s attempting to maintain alive. It was a reputation that he says displays the way in which he has lived. “Agó Acoé Inó,” which implies “canine with out an proprietor.” His daughter leaned in to ensure he spelled it accurately.

“She is aware of greater than me now,” he mentioned, laughing. “We gained’t lose Chaná.”