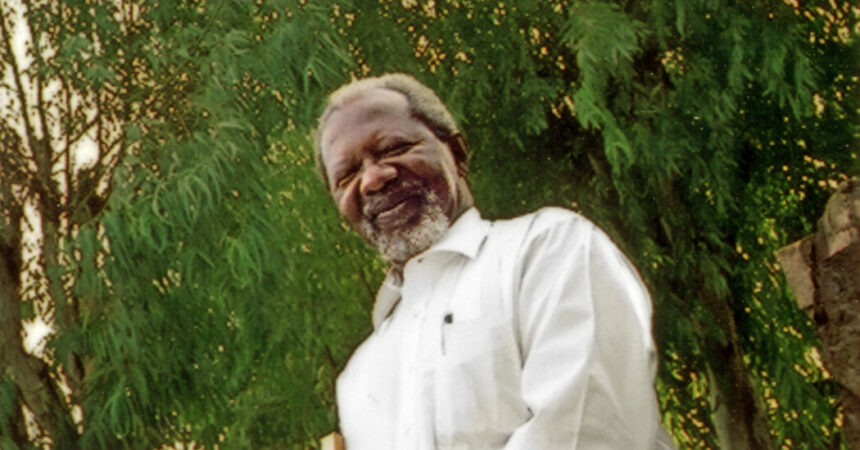

Paulin Hountondji, a thinker from Benin whose critique of colonial-era anthropology helped remodel African mental life, died on Feb. 2 at his dwelling in Cotonou, Benin’s largest metropolis. He was 81.

His loss of life was confirmed by his son, Hervé, who didn’t cite a trigger.

As a younger philosophy professor on a continent that was throwing off the colonial grip within the Sixties, Mr. Hountondji (pronounced HUN-ton-djee) rebelled towards efforts to drive African methods of pondering into the European worldview. Himself steeped in European thought — he was the primary African admitted as a philosophy pupil on the most prestigious college in France, the École Normale Superieure — he developed a critique of what he known as “ethnophilosophy,” a concoction of Europeans.

His work has formed the examine of philosophy in Africa ever since. It turned a form of second declaration of independence for Africa — an mental one this time — within the view of the African philosophers who’ve adopted Mr. Hountondji. It was “essential and really liberating,” the Columbia College thinker Souleyman Bachir Diagne mentioned in an interview.

In his introduction to the e-book “Paulin Hountondji: Leçons de Philosophie Africaine,” by Bado Ndoye (printed in 2022 however not but translated into English), Mr. Diagne known as him “probably the most influential determine in philosophy in Africa.”

A modest man who spent his profession instructing in African universities, principally at Benin’s nationwide college, with temporary forays into the turbulent politics of his small West African coastal homeland, Mr. Hountondji knew that there was one thing amiss in efforts by Europeans to inform Africans how they need to take into consideration their place within the universe.

He additionally knew that the rising strongman rule of the Sixties, with its enforced groupthink, spelled bother for the continent. He discovered the roots of that concept of collective thought — wrongly thought of a pure attribute of Africans — within the “ethnophilosophy” that he so strongly criticized.

Armed along with his work on the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, in his late 20s and early 30s Mr. Hountondji undertook to confront head-on “Bantu Philosophy,” a e-book by a Belgian missionary priest, Placide Tempels, that for practically 30 years had set the tone for African philosophy.

When Father Tempels, an ecclesiastical insurgent who lived for many years in what’s now the Democratic Republic of Congo, printed “Bantu Philosophy” in 1945, it was seen by a primary era of pre-independence African intellectuals as groundbreaking. It purported to revive mental dignity to a continent seen as “primitive” within the colonialist worldview.

Opposite to European perception that Africans had been incapable of summary thought, Father Tempels advised that they really did have a philosophy, a method of seeing themselves within the universe.

However in a collection of essays starting in 1969 and picked up within the e-book “African Philosophy: Fantasy and Actuality” (printed in 1976 in French and in 1983 in English), Mr. Hountondji got down to demolish the Belgian priest’s work as not more than ethnographic musings that in the end bolstered colonialism.

Whether or not or not one agreed with Father Tempels’s central thesis — that for the “Bantu,” or African, “being” means “energy” — his complete strategy was flawed, Mr. Hountondji argued. Philosophy can’t emanate from a gaggle, he wrote, however should be the duty of particular person philosophers, an concept influenced by Mr. Hountondji’s data of Husserl.

However that duty was absent in Father Tempels’s largely nameless band of “Bantus,” he mentioned.

In a memoir, “Combats Pour le Sens: Un Itineraire Africain” (1997), printed in English in 2002 as “The Battle for Which means: Reflections on Philosophy, Tradition and Democracy in Africa,” Mr. Hountondji rejected “the development, as a norm for all Africans, previous, current and future, of a type of pondering, a system of beliefs, which might at finest solely correspond to an already decided stage of the mental journey of Black peoples.”

So, Mr. Hountondji wrote, “what was thus offered as ‘Bantu philosophy’ was probably not the philosophy of the Bantu, however of Tempels, and engaged solely the duty of the Belgian missionary, having develop into, for the event, the analyst of the methods and customs of the Bantu.”

These ideas had the impact of a bomb in African mental life. Mr. Hountondji was criticized for elitism, for “Eurocentrism” and for rejecting Africa’s oral traditions. However these criticisms quickly fell by the wayside, and right now his “critique of ethnophilosophy enjoys canonical standing in up to date African philosophy,” Pascah Mungwini wrote in his 2022 survey, “African Philosophy.” He known as it a “philosophical masterpiece.”

African thinkers had been free of an immemorial set of beliefs to which European thinkers like Father Tempels, and the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, had chained them.

“What the Belgian Franciscan was providing was actually a system of collective thought, which was supposedly a optimistic African attribute,” Mr. Hountondji instructed Radio France Internationale in a 2022 interview. “This isn’t the sense of the phrase ‘philosophy.’”

Mr. Hountondji “needed the purity of the concept,” Mr. Diagne mentioned. “What needed to be cleared away was all of the picturesque of ‘anthropology.’’’

Within the early Seventies, Mr. Hountondji taught philosophy at universities in what was then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The nation was then “dwelling underneath the boot of a common,” Mobutu Sese Seko, who used “conventional ‘philosophy’ to justify or cover the worst excesses, probably the most atrocious human rights violations,” Mr. Hountondji wrote in his memoir.

Mr. Hountondji’s “refusal of the unanimist message” within the Zaire of Basic Mobutu, as Mr. Diagne put it, echoed his rejection of the missionary Father Tempels, who, like the final, advised that Africans all spoke with one voice.

These reflections on autocracy and the enforced political assist it entails influenced Mr. Hountondji’s reluctant entrance into public life in Benin, the place, as a professor on the Nationwide College, he had chafed underneath the Marxist-Leninist dictatorship of Gen. Mathieu Kérékou. What Mr. Hountondji known as Basic Kérékou’s “regime of terror” ended after a 1990 nationwide convention of Benin residents summoned by the final unexpectedly turned towards him.

Mr. Hountondji was invited to the convention and instantly zeroed in on the central situation, to the displeasure of the final’s subordinates: whether or not the gathering might resolve the nation’s future. Mr. Hountondji’s was the “solely reliable and attainable resolution,” the historian Richard Banegas wrote in “La Démocratie au Pas de Caméléon” (2003), his political historical past of Benin.

Mr. Hountondji’s facet received, and Benin turned a democracy — for a time. Mr. Hountondji unexpectedly discovered himself minister of training within the new authorities, from 1990 to 1991, and minister of tradition and communication from 1991 to 1993.

He was unsuited to political life, his son, Hervé, mentioned in an interview, as a result of “it was out of the query for him to close himself up in a political get together.” Mr. Hountondji wrote in his memoir that at some point he would develop his ideas on “the cynicism, the hypocrisy, the day by day lies, which make up day by day political life.” He by no means did.

He went again to instructing on the nationwide college, now the Université d’Abomey-Calavi, the place he was to stay for the remainder of his profession.

Paulin Jidenu Hountondji was born on April 11, 1942, in Treichville, now a part of Abidjan in Ivory Coast, to Paul Hountondji, a pastor within the Methodist Church, and Marguerite (Dovoedo) Hountondji.

He acquired his baccalauréat (the equal of a highschool diploma) on the Lycée Victor-Poll, a faculty the place the nation’s elite had been educated, in Porto-Novo, Benin’s capital. He went on to earn a level in philosophy from the École Normale Superieure in Paris in 1967 and his doctorate in philosophy from the College of Paris underneath Paul Ricoeur, with a thesis on Husserl, in 1970.

As a pupil in Paris within the first days of African independence, Mr. Hountondji wrote, he grew disturbed by the willingness of different African college students to paper over the crimes of one of many continent’s new heroes, the Guinean dictator Sekou Touré, who was to wind up driving a lot of his nation into exile.

Mr. Hountondji taught philosophy on the Nationwide College of Zaire in 1971 and 1972 earlier than returning to his native Benin. From 1998 till his loss of life he was director of the African Heart for Superior Research in Porto-Novo.

Along with his son, he’s survived by a daughter, Flore, and his spouse, Grâce (Darboux) Hountondji. Two former presidents of Benin spoke at his funeral in Cotonou on March 1.

In later years, Mr. Diagne mentioned, Mr. Hountondji “believed he had gone too far in his radicality” in his earlier skepticism of African oral traditions.

But he remained agency to the tip that Europeans shouldn’t be doing the pondering for Africans. “There’s a colonialist viewpoint that every one Africans agree with one another, and have the identical mind-set,” Mr. Hountondji instructed French radio in 2022. “The colonialist view is insensitive to the plurality of opinions in an oral civilization.”

Flore Nobime contributed reporting from Cotonou.