Giorgio Napolitano, trendy Italy’s longest-serving president, who orchestrated the switch of energy from a scandal-scarred Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi to a little-known economist in a 2011 debt disaster and turned his nation again from the brink of collapse, died on Friday in Rome. He was 98.

His demise, in a clinic, was introduced by Italy’s present president, Sergio Mattarella, who stated in a press release that Mr. Napolitano’s “life mirrors a big a part of the historical past within the second half of the 1900, with its dramas, its complexity, its objectives and hopes.”

After a half-century in public life, Mr. Napolitano was caught up in a wierd paradox. A former high-ranking chief of Italy’s Communist Occasion, he was instrumental in saving Europe’s third-largest capitalist economic system from spoil. And he did it with out government energy, utilizing solely the authority of an institutional head of state and guarantor of the Structure.

On the merry-go-round of Italian politics, the place leaders and governments revolved with mind-boggling rapidity, Mr. Napolitano by no means reached for the golden ring of the prime minister’s workplace and by no means acquired the polish of premiers like Giulio Andreotti, Amintore Fanfani or Mr. Berlusconi, the flamboyant billionaire media magnate and womanizer who was convicted of tax fraud after his resignation. Mr. Berlusconi died at 86 in June.

Certainly, to unusual Italians and to a world cognoscenti, Mr. Napolitano was fairly the alternative of such males: a down-to-earth, straight-talking mental who had served 38 years in Parliament, written a dozen books, helped ease Italian communism right into a social democratic motion, supported nearer ties to the European Union and America, and was president of the republic for practically 9 years, from 2006 to 2015.

Beneath Italy’s postwar Structure, the president is elected by Parliament for a seven-year time period. Whereas second phrases should not barred by legislation, no president had ever been re-elected till Mr. Napolitano was, in 2013.

Whereas he had few day-to-day powers, he had authority in a disaster to dissolve Parliament, name elections and select a main minister to kind a brand new authorities — processes unfamiliar to many outsiders however routine to Italians, who’ve seen greater than 60 governments come and go since World Battle II.

The disaster in 2011 had been constructing for months, even years. By autumn, Italy’s public debt had shot as much as $2.6 trillion, among the many highest in Europe, and borrowing charges — the value demanded by buyers to lend cash to Italy — had soared to greater than 7 %. That was the very best degree because the adoption of the euro a decade earlier, and near ranges that had compelled different eurozone international locations to hunt bailouts.

Fiscal catastrophe loomed for Italians, with the prospect of rising taxes and inflation in addition to cuts in jobs, wages and pensions. Economists additionally feared {that a} collapse in Italy would unfold panic throughout Europe and world wide. Mr. Berlusconi’s fourth authorities since 1994 proposed austerity measures, however his political energy, eroded by years of sexual and monetary scandals, started to unravel.

Anticipating the worst, Mr. Napolitano had for months been laying the groundwork for a transition — consulting with Italian political and monetary leaders, European governments, American officers and the Financial institution of Italy, assaying doable candidates and making ready a recent financial agenda and a viable different to the Berlusconi authorities. Whereas the disaster gathered steam slowly, the top got here rapidly.

Mr. Berlusconi’s austerity finances failed in Parliament, was modified for deeper cuts and, after weeks of stalemate, was adopted on phrases sought by the European Union. Defections from the prime minister’s coalition doomed his tenure. With the debt disaster closing in and Mr. Berlusconi’s as soon as mighty political capital spent, it turned clear that his authorities couldn’t survive a vote of confidence.

On Nov. 12, 2011, Mr. Berlusconi tendered his resignation to Mr. Napolitano on the Quirinale Palace, the presidential seat in Rome. Exterior, crowds cheered and popped Champagne corks, an impromptu orchestra and choir struck up the “Hallelujah” refrain from Handel’s “Messiah,” and mopeds and vehicles sped by means of the middle of Rome, honking horns and waving Italian flags in celebration.

Mr. Berlusconi’s substitute was ready within the wings. The following day, Mr. Napolitano nominated a brand new prime minister, Mario Monti, an economist, president of the revered Bocconi College in Milan and former member of the European Fee, the European Union’s government physique. He already had a proposed slate of consultants for his cupboard and plans for financial reforms.

“Now could be the time to point out most duty,” Mr. Napolitano stated in his announcement. “It isn’t the time to repay outdated scores, nor for sterile partisan recriminations. It’s time to re-establish a local weather of calmness and mutual respect.”

Parliament rapidly accepted — and Mr. Napolitano swore in — Mr. Monti’s new authorities, composed principally of lecturers, bankers and top-level civil servants, all consultants of their fields. Mr. Napolitano additionally organized to have Mr. Monti, a person from academe, appointed a senator for all times.

“That was an act of genius,” Corrado Augias, an Italian author and commentator, advised The New York Occasions. “He took a professor and redressed him as a politician.”

The change of prime ministers hardly solved Italy’s monetary issues. However within the coming months Mr. Monti’s authorities raised taxes, reformed pensions, lower bills and started to revive market confidence in Italy’s eventual capability to pay its money owed.

Mr. Napolitano’s maneuvers have been hailed as essential to the way forward for Italy’s fiscal stability. President Barack Obama, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany and President Nicolas Sarkozy of France all known as him to precise help for his management. Italians got here to treat him as an embodiment of civic advantage. His approval scores rose to above 80 %. Italian Wired journal named him its “Man of the Yr.”

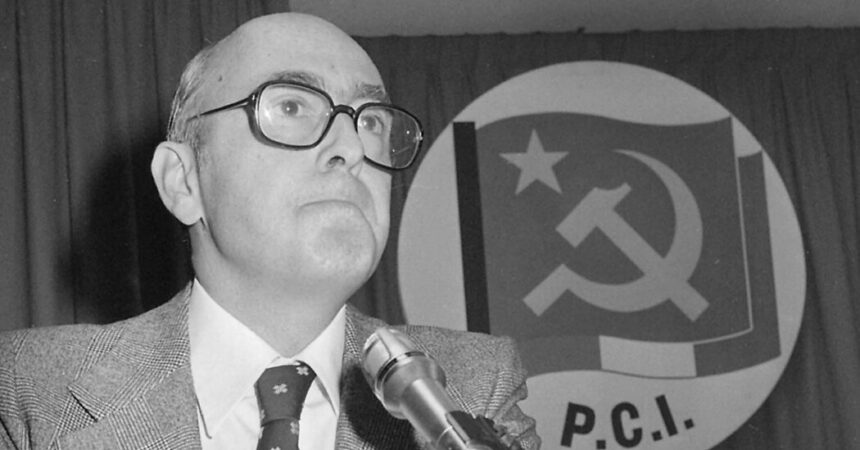

Giorgio Napolitano was born in Naples on June 29, 1925, to Giovanni and Carolina (Bobbio) Napolitano. His father was a lawyer, and his mom was a descendant of Piedmont the Aristocracy. He grew up hating Mussolini’s Fascist dictatorship and have become a resistance fighter whereas finding out on the College of Naples. In 1945, he joined the Italian Communist Occasion (P.C.I.), and two years later he obtained his legislation diploma.

After working for land reforms in depressed Southern Italy, he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, the decrease home of Italy’s legislature, in 1953 as a Communist consultant from Naples. In 1956, his get together supported the Soviet repression of Hungary’s rebellion; Mr. Napolitano later stated he regretted that stance and have become a average in get together affairs.

He’s survived by his spouse, Clio Maria Bittoni, whom he married in 1959; their sons, Giovanni and Giulio; and two grandchildren.

Within the Nineteen Seventies and ’80s, Mr. Napolitano was a member of the Italian Communist Occasion’s Central Committee, directing financial insurance policies, worldwide relations and cultural affairs. He and the get together veered away from Soviet Communism, lastly broke with Moscow and advocated a socialist interdependence of European international locations.

He made the primary of a number of visits to the USA in 1978, to lecture and to satisfy journalists and officers. The previous secretary of state Henry A. Kissinger known as him his “favourite Communist.”

As Soviet Communism crumbled, Mr. Napolitano was Italy’s delegate to the European Parliament from 1989 to 1992. When the Italian Communist Occasion lapsed in 1991, he joined its successor, the Democratic Occasion of the Left, and have become speaker of the Chamber of Deputies.

By 1996, when he left Parliament, he was broadly considered the physique’s anchor of stability. He was given the publish of inside minister, the primary politician with Communist roots in that law-and-order publish. A decade later, at 81, he reluctantly accepted the Italian presidency. After deciding on Mr. Monti to succeed Mr. Berlusconi, he picked two extra prime ministers, Enrico Letta in 2013 and Matteo Renzi in 2014, earlier than retiring in 2015.

Mr. Napolitano’s books, most of them about politics and authorities, included a memoir, “From P.C.I. to European Socialism” (2005), and “One and Indivisible: Ideas on 150 Years of Our Italy” (2011).

Elisabetta Povoledo and Gaia Pianigiani contributed reporting.