Some authors you’re keen on for his or her fireplace; some you’re keen on for his or her ice. J.M. Coetzee, the South African-turned-Australian novelist, has spent half a century engaged with the most important questions of human motive and human dignity, however his novels should not what you’d name grand. They’re smooth, unadorned, unfailingly exact; most high out at 200 pages or so; the sentences have been knapped to their sharpest. Stylistically, his novels are fairly brisk. Morally, they’re heavyweights.

Coetzee was born in Cape City in 1940, right into a household of what he has referred to as “recusant Afrikaners”: They spoke English moderately than Afrikaans at dwelling. By the Nineteen Eighties his spare, stinging prose had received worldwide acclaim as considered one of literature’s strongest responses to apartheid, although extra militant South African writers had been doubtful of his ambiguity and discretion. He’s now received each literary gong obtainable (a Nobel in 2003, two Bookers earlier than that), and has pretty much as good a declare as anybody to be probably the most vital residing writer in English — a language about which he has currently grown ambivalent.

For those who’re new to Coetzee, we’d higher begin with the obvious matter: It’s pronounced kuut-SAY, two syllables, rhyming with “day,” not with “thought.” The J stands for John, and the M — effectively, we now realize it stands for Maxwell, however for many years he let folks consider it was Michael. That unintended alias is the primary of many private and literary feints, and he has all the time leavened the seriousness of his prose with metafictional evasions.

His 15 novels (together with three volumes of autobiography that may as effectively be fiction, plus essays on censorship, race, linguistics and psychology) embody head-on realist fictions of South Africa throughout apartheid and after. However there are additionally Coetzeean stand-ins each female and male, characters who migrate from one airplane of existence to a different, and extra shattered fourth partitions than on HGTV’s “Flip or Flop.” The books written since his transfer to Australia in 2002, particularly, have the schematic fantastic thing about Heinrich von Kleist’s marionette theater. (This abstraction is one motive that the film variations of Coetzee’s novels are universally horrible — the “Shame” with John Malkovich really lives as much as its title — whereas extra indirect diversifications, reminiscent of operas of “Ready for the Barbarians” and “Gradual Man,” have fared higher.)

I’m positive it says one thing about me that my favourite novelist is thought for works of unrelieved seriousness, psychological extremity and reliably joyless intercourse. He’s the final author it is best to go to for lush description or richly drawn panorama. (Right here is an instance of scene-setting in “The Pole,” his new novella: “It’s a nice autumn day. The leaves are turning, et cetera.”)

However Coetzee is not any misanthrope and no Gloomy Gus: a popularity which will come extra from his aversion to interviews and prizes than his fiction anyway. As together with his early hero Samuel Beckett, there’s an important fact — even, consider me, an optimism — within the muscle groups of Coetzee’s fat-free prose. (Additionally like Beckett, Coetzee has a darkish humor that’s very underrated; if you find yourself buried to your neck in sand, you gotta chuckle.) Right here’s the place to begin.

I like dystopia.

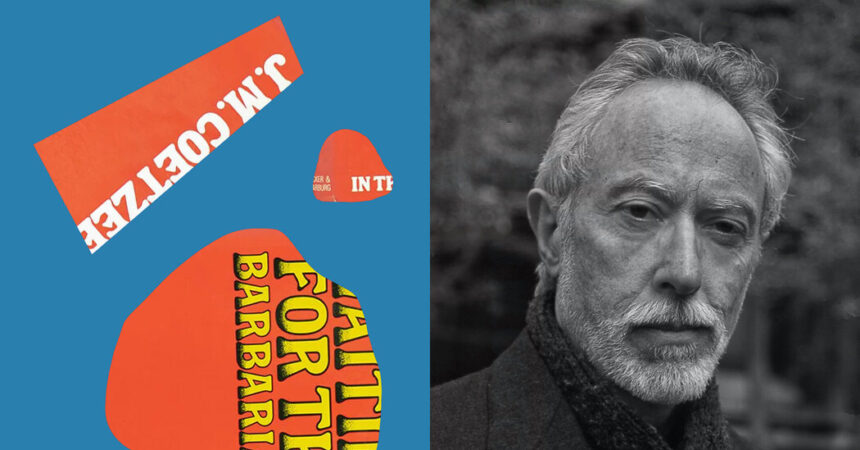

After two early novels with some showy, youthful acrobatics (twinned narratives, numbered paragraphs), Coetzee revealed the extreme, dislocated “Ready for the Barbarians” (1980). From its first line — “I’ve by no means seen something prefer it: two little discs of glass suspended in entrance of his eyes in loops of wire” — we’re plunged right into a third-tier dusty frontier city of some authoritarian empire, so removed from the capital that even sun shades are a novelty. The native Justice of the Peace has been a dutiful, if concupiscent, colonial administrator. However the fanatical Colonel Joll (he with the sun shades) turns into obsessive about heading off a supposed barbarian invasion. His marketing campaign of terror forces the Justice of the Peace into an ethical dilemma that may value him way more than his job.

This e-book is lean and imply; as regards dystopian brutality, it makes “The Handmaid’s Story” appear to be “Little Ladies.” However Coetzee’s paranoid and segregated empire is not an allegory for apartheid South Africa — certainly, that was what irritated his South African critics most. Sure, the true “barbarians” are the empire’s males, however there’s a bigger and extra troubling universality to Coetzee’s torturers, and to our personal wishes to examine them. “The darkish, forbidden chamber,” Coetzee wrote in a 1986 essay for this publication, “is the origin of novelistic fantasy per se.”

Present me what apartheid did to the soul.

It is best to learn “Life & Occasions of Michael Okay” (1983), the rangy parable of dignity and diminishment for which he received the primary of his two Bookers. Michael Okay is a gardener in Cape City whose mom is a housekeeper in in poor health well being. They attempt to go away town for the Swartberg Mountains, however she doesn’t survive the journey, and Okay falls into a foul dream of bureaucracies and brutality. In contrast to in “Ready for the Barbarians,” right here we’re in up to date South Africa — besides this South Africa has fallen into civil struggle, the place whites-only suburbs have been ransacked and the apartheid-state flag flies over detention camps. (Okay’s race is rarely specified outright, although the context makes clear he’s of blended white, Black and Asian heritage.)

This was 1983. Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu had been nonetheless in jail; worldwide boycotts had been efficiently concentrating on South African athletes and artists; the apartheid state was combating not solely its Black majority, however guerrillas in Namibia and Angola. A civil struggle was hardly unthinkable, and the one Coetzee imagined was as silly because it was violent, working on effectively after the oppressors had misplaced the need to battle. (Much more than the imperialists in “Ready for the Barbarians,” the whites in “Michael Okay” know they’re doomed.)

Gradual-witted however unwilling to yield, Okay abandons society and lives, barely, off the land — shriveling right into a size-zero Crusoe who should embrace insignificance as the value of being free. It’s a unusual exaltation of freedom, this small lifetime of Okay’s. And but in decreasing one man to the pith of animal existence, Coetzee wrote one of many few books I do know that deserves probably the most clichéd of all reward: life-affirming.

Hold it quick, however give me all the things.

Breathless, bedraggled, her petticoat heavy with saltwater, the castaway Susan Barton washes ashore on an island off the coast of Brazil, however two males are already there: the Englishman Robinson Cruso (no E), and his man Friday (no tongue). The trio are rescued. On the voyage dwelling Cruso dies. Marooned in London, Susan has nothing however “all that Cruso leaves behind, which is the story of his island.” She tries with out success to jot down, whereas Friday — Cruso mentioned slave-traders had mutilated him; Susan has her doubts — appears to haven’t any language in any respect. They have to flip to a morally doubtful and deeply indebted ghostwriter: one Daniel Foe, whose views on literature and the marketplace for true tales will cleave her ceaselessly from Cruso’s isle.

I’m ever and all the time in love with “Foe” (1986), which, from a naked plot abstract, could sound like considered one of many the-empire-writes-back sequels of the English canon — Jean Rhys’s “Broad Sargasso Sea” (an Antillean “Jane Eyre”), Peter Carey’s “Jack Maggs” (an Antipodean “Nice Expectations”). Two generations of comp-lit college students have gorged now on the novel’s irresolvable tangle of speech and writing, gender and colonialism, and wrung each drop of concept from its fewer than 160 pages. However “Foe,” written in a unprecedented ventriloquism of 18th-century English, is a lot greater than a postcolonial just-so story, and way more, too, than a reverse Robinsonade.

Who’s an writer, and who has a “life story”? From its three-letter title on, Coetzee’s shortest and biggest novel is about how artwork and life will all the time be at odds. It’s concerning the irresistible seductions of bankrupt writers, and literature’s inadequate promise to point out you one other world. And above all, this inexhaustible novel is about find out how to maintain onto your true self when new media — the novel within the 18th century, the TikTok account within the twenty first — wish to warp your life right into a narrative on the market.

I wish to know his actual life — or as near it as I can get.

Coetzee has written three volumes of autobiography — however at least the novels, these ostensible memoirs (all narrated within the third particular person, a “he” held at arm’s size) have a shifty relationship with the reality. “Boyhood” (1997) relates the writer’s life from ages 10 to 13, with sad days in school and a deep alienation from his father relieved by means of rapturous journeys to the Karoo, the Western Cape’s arid farm nation. “Youth” (2002) follows a 20ish Coetzee to London, the place he strikes out with the women.

The final, finest, and strangest of the three is “Summertime” (2009), which ostensibly covers the Seventies, his return to South Africa and his preliminary efforts at fiction. But it surely appears the writer named on the quilt is already lifeless; the e-book includes 5 interviews with former lovers, college students and acquaintances, performed by a biographer of “the late John Coetzee.”

I can deal with him at his bleakest. (I assume.)

For the 50-something professor David Lurie, a mastery of English Romantic poetry appears to supply an moral exemption for seducing considered one of his college students, whose diploma of consent we might generously name ambiguous. The affair is uncovered; Lurie loses his job (after a terrifically drawn scene of a college tribunal, with all of the darkish comedy of Kafka); he leaves Cape City to affix his daughter, Lucy, on her farm within the Jap Cape. However then comes one other act of sexual violence, way more brutal than his personal transgression — and as Lucy considers her well-being, her father should cleanse the gangrenous basis of his ethical life.

In contrast to his equivocal Nineteen Eighties fictions, “Shame” (1999) demanded to be learn in mild of up to date South Africa: a brand new multiracial democracy, engrossed within the public hearings of the Fact and Reconciliation Fee. When David begs his daughter to go to the police, Lucy insists she should not report her gang rape “on this place, at the moment … this place being South Africa.” I can’t lie, this e-book is bleak — however so is “Oedipus Rex.” There could be a magnificence in bleakness, and the austere fatalism of “Shame” has made it one of the crucial debated novels of the final 30 years.

It netted Coetzee Booker No. 2 (as with the primary time, he didn’t trouble to select it up) and a public renown he manifestly disliked. It additionally elicited indignant opposition in South Africa: from the highest of the African Nationwide Congress, who decried its “racism” to the U.N., and from white conservatives who thought they had been the actual victims. At this time, although, its extra quick worth could lie in its scrutiny of gender: “Shame” is, in fact, a proto-MeToo novel, all concerning the wishes and deficiencies of males, and the private and non-private cancellations they might carry upon themselves.

“Shame” additionally inaugurates a significant theme of Coetzee’s later writing: the connection of people to animals, examined with a thinker’s rigor in “Elizabeth Costello” and in his quick fiction. If Lurie finds even the slightest absolution — or grace, the title’s not-quite-opposite — it’s in a veterinary clinic, caring for animals in a world the place males are canine.

How about his criticism?

In his novels Coetzee evades, contorts, ironizes; in his nonfiction, he has the exactitude of the surgeon. “White Writing: On the Tradition of Letters in South Africa” (1988), probably the most authentic of his a number of collections of essays, research the novels of “folks now not European, not but African,” and the nationwide and racial mythmaking of white novelists working in each English and Afrikaans. (The majority of the novels he research, by authors reminiscent of Sarah Gertrude Millin and C.M. van den Heever, had been written earlier than the establishment of apartheid in 1948.)

There are syrupy miscegenation tragedies, there may be repellent crypto-anthropology concerning the lazy natives and the industrious Dutch, but Coetzee’s key object of research is the plaasroman, or “farm novel” in Afrikaans. In these settlers’ pastoral tales, the South African soil is mythologized and feminized, but it surely’s a harsh and “infertile” Earth Mom that appears to reject even the lifeless. I worth “White Writing,” particularly, as a mannequin for a way a critic ought to have interaction with racist works from the previous: no dismissal, no excuses both, only a calm and unflinching publicity of their deadly contradictions. “Our craft,” as Coetzee writes right here, “is all in studying the opposite: gaps, inverses, undersides; the veiled, the darkish, the buried, the female; alterities.”

I’m not afraid to get somewhat bizarre.

Coetzee has had a captivating third act since immigrating to Australia within the 2000s; his books have grown extra experimental and philosophical, mixing fiction with nonfiction and sometimes defying conventional novelistic construction. Crucial of his Australian novels — a e-book of actual energy and deep thriller — is “The Childhood of Jesus” (2013), the primary in a trilogy of weird and deadpan tales a couple of boy and a person making new lives in a world “washed clear.”

Like everybody in Novilla, the featureless city they’ve arrived at by boat, Simón and David are refugees whose reminiscence has been erased, mastering the rudiments of a brand new language. (That language is Spanish — and not too long ago, as somewhat private protest in opposition to the hegemony of English, Coetzee has been releasing his novels in Spanish greater than a 12 months earlier than they arrive out within the authentic.) Simón introduces the boy to a girl, Inés, and in an outlandish parody of the Annunciation convinces her that she is David’s mom. However David’s conduct … effectively, it’s not fairly divine. He’s an entitled brat with a critical hangup about arithmetic, propounding a mystical perception that numbers are “islands in a fantastic black sea of nothingness,” past the attain of arithmetic.

This e-book, and the 2 that comply with it, are quixotic, within the authentic sense: “Don Quixote,” or not less than a kids’s adaptation of it, figures centrally in David’s private gospel. Much more than “Ready for the Barbarians,” this one snaps all allegorical readings earlier than you possibly can say Noli me tangere. But “The Childhood of Jesus” brings dwelling so lots of the themes which have animated Coetzee since 1970: above all, the strain between emotion and motive. There’s an ardor that may lie behind even the best austerity.