This text is a part of Missed, a collection of obituaries about outstanding folks whose deaths, starting in 1851, went unreported in The Instances.

It’s April 17, 1945. Two Nazi officers are making a 24-year-old girl stroll forward of them towards the sandy dunes alongside the Dutch coast. She’s carrying a blue skirt and a purple and blue sweater.

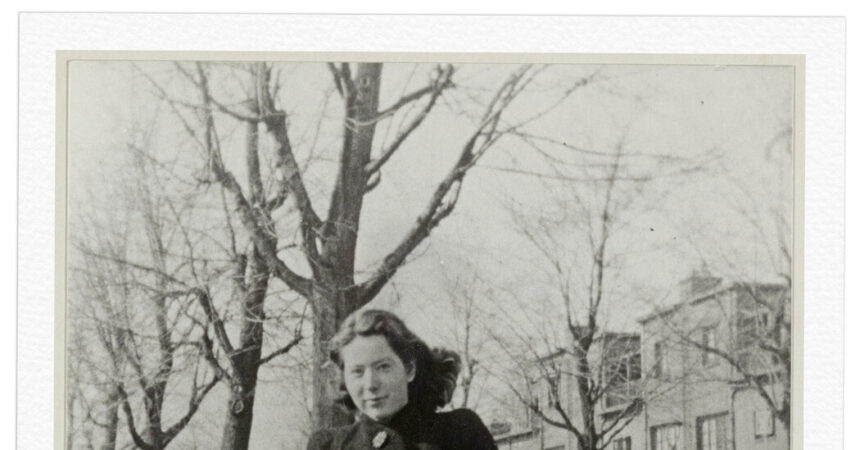

She is the Dutch resistance fighter Hannie Schaft, however one won’t have acknowledged her instantly: Her signature purple hair has been dyed black.

As she walks, one of many officers fires his gun behind her head. The bullet ricochets off her cranium and doesn’t kill her. The opposite officer then shoots her, additionally at the back of the top, this time at nearer vary.

That’s how Hannie Schaft died, only a few weeks earlier than the top of World Battle II in Europe. She had been arrested and despatched to a jail in Amsterdam a couple of month earlier, throughout a random verify in Haarlem, her hometown within the Netherlands, when she was discovered carrying a gun, in addition to unlawful newspapers and pamphlets from the resistance motion, in her bicycle bag. Initially it wasn’t apparent to the Nazis whom they’d arrested, but it surely quickly grew to become evident that it was the lady they’d been on the lookout for, the lady often known as the “lady with the purple hair,” who had shot and killed a number of Nazis and collaborators.

She was born Jannetje Johanna Schaft on Sept. 16, 1920, in a left-wing, middle-class family, to Aafje Talea (Vrijer) Schaft, a homemaker with a progressive streak, and Pieter Schaft, a instructor. Hannie, a reputation she adopted when she grew to become a resistance fighter, had an older sister, Annie, who had died of diphtheria. Consequently, she had a protecting childhood, mentioned Liesbeth van der Horst, the director of the Resistance Museum in Amsterdam, which has a show about Schaft that features her glasses, a model of the gun she carried, and a photograph of her and a fellow resistance fighter.

“She was a critical, principled lady,” van der Horst mentioned in an interview. “She was a bookworm.”

She added that regardless of being shy, Schaft “was happy with her purple hair” and the way it helped her stand out.

After highschool in Haarlem, Schaft studied regulation on the College of Amsterdam, within the hopes of turning into a human rights lawyer. She was a pupil when the Nazis occupied the Netherlands in Might 1940, plunging the nation into battle and concentrating on Jewish residents. Although Schaft was not Jewish, the occupation set her on a path to political activism.

“Because the Nazi regime’s insurance policies acquired harsher towards Jews, her personal sense of ethical outrage grew stronger,” mentioned Buzzy Jackson, the writer of “To Die Stunning” (2023), a novel about Schaft’s life. “She began to wish to do extra.”

She started volunteering for the Pink Cross, rolling bandages and making first assist kits for troopers and serving to German refugees. When the Nazi regime required all college students within the Netherlands to pledge their loyalty to the occupiers, Schaft, like many others, refused to take action and was pressured to drop out.

She maintained the friendships she had shaped with two Jewish women on the college, serving to them acquire pretend IDs to evade Nazi checkpoints and hiding them because the Nazis continued stripping Jewish residents of their fundamental rights.

By the top of the battle, greater than 100,000 folks — practically 75 p.c of all Dutch Jews, the very best proportion of any Western European nation — could be deported to focus camps and murdered.

The resistance, van der Horst mentioned, was not one organized motion however somewhat a tangle of overlapping networks.

Schaft joined the Resistance Council, a communist group, the place she met two sisters, Truus and Freddie Oversteegen, who grew to become her shut associates and would survive the battle. (In March, the Netherlands Institute for Battle Documentation introduced that it had discovered two letters written by Truus Oversteegen to a good friend, through which she talked about Schaft.)

The armed resistance was a particularly harmful endeavor, with many fighters arrested and executed. It’s unclear what number of assaults could be attributed to Schaft, however researchers say there have been at the very least six.

In June 1944, Schaft and a fellow resistance fighter, Jan Bonekamp (with whom she was rumored to have had a romantic relationship), focused a high-ranking police officer for assassination. Because the officer was getting on his bicycle to go to work, Schaft shot him within the again, inflicting him to fall off the bike. Bonekamp completed the killing however was injured doing so. He died shortly after. Schaft managed to flee on her personal bike, which was how she acquired round doing her resistance work.

Schaft was additionally concerned in killing or wounding a baker who was recognized for betraying folks, a hairdresser who labored for the Nazis’ intelligence company, and one other Nazi police officer.

Earlier than confronting her targets, Schaft placed on make-up — together with lipstick and mascara — and styled her hair, Jackson mentioned. In one of many few direct quotations which have been attributed to Schaft, she defined her reasoning to Truus Oversteegen: “I’ll die clear and exquisite.”

Daybreak Skorczewski, a lecturer at Amsterdam College School, mentioned Schaft’s involvement within the resistance was notably extraordinary as a result of few ladies within the motion took up arms.

“It’s uncommon {that a} girl of her age would begin killing Nazis in alleyways,” she mentioned in a video name.

As soon as the Nazis began on the lookout for “the lady with the purple hair,” as she was described on their most-wanted checklist, Schaft disguised herself by dying her hair black and carrying wire-frame glasses.

The Nazis raided Schaft’s dad and mom’ home and arrested them, hoping that she would flip herself in, however they have been launched 9 months later, based on the Resistance Museum.

After Schaft was caught, she admitted her resistance actions. However there is no such thing as a proof that she gave the Nazis details about any of her fellow resistance fighters.

After the liberation of the Netherlands on Might 5, 1945, Schaft’s physique was dug up from a mass grave with tons of of different folks the Nazis had executed. She was the one girl amongst them.

Later that yr, she was buried on the Honorary Cemetery within the seaside city of Bloemendaal, alongside tons of of different resistance fighters. Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands attended the service, based on paperwork within the Dutch Nationwide Archives.

Schaft’s title is well-known within the Netherlands. There are streets and colleges named after her, and in 1981 she was the topic of a scripted film referred to as “The Lady With the Pink Hair.” (Janet Maslin panned the movie in The New York Instances, writing that Schaft’s story “was undoubtedly extra thrilling in actuality than it’s on the display screen.”) An Amsterdam-based postproduction firm is planning to shine the unique movie and rerelease it for the Netherlands Movie Pageant in September.

Her story remains to be being uncovered by researchers — a difficult job as a result of resistance fighters labored undercover and infrequently left little proof behind.

As Jackson, the writer of “To Die Stunning,” famous, “The explanation we learn about Anne Frank is as a result of she left a diary.”

Schaft, alternatively, made it some extent to not put something in writing. “That’s true for most individuals within the resistance,” Jackson mentioned. “There aren’t loads of data to take a look at.”