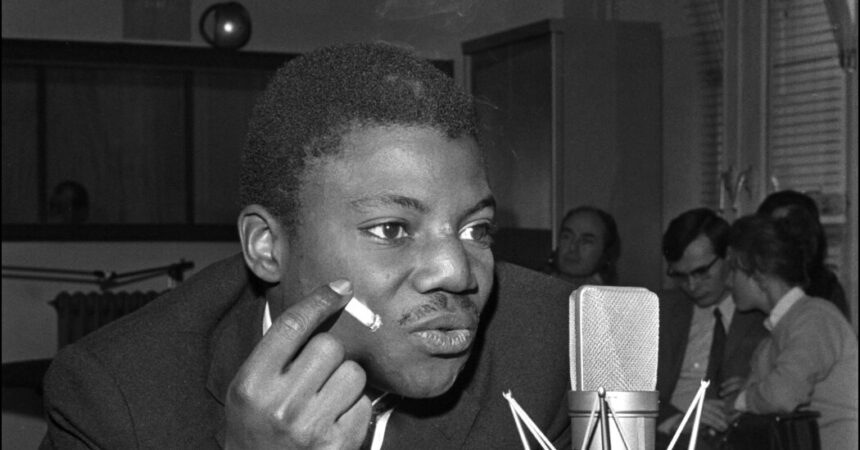

In 1968, a younger Malian creator residing in Paris revealed his first ebook to the best reward: Critics referred to as it a “nice African novel,” and awarded it one among France’s most prestigious literary prizes. However quickly, his rise gave technique to a devastating fall from grace.

The creator, Yambo Ouologuem, was accused of plagiarism, however he denied any wrongdoing and refused to clarify himself. His publishers in France and the US withdrew the novel, “Le Devoir de Violence,” or “Certain to Violence.” After a crushing decade, Ouologuem returned to Mali, the place he remained resolutely silent on the matter, responding to questions on his aborted literary profession with digressions or outbursts of anger, refusing even to talk French.

He died in 2017, forgotten by most, his novel learn by few — till lately, when one other award-winning novel by a West African creator helped deliver new consideration to Ouologuem and the tormented trajectory of his ebook. “The Most Secret Reminiscence of Males,” by the Senegalese author Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, follows a mysterious author who disappears from public life after being accused of plagiarism in Paris — a free reference to Ouologuem. It gained the Goncourt prize in 2021 and was revealed in the US by Different Press this week, in a translation by Lara Vergnaud.

With Sarr’s ebook, Different Press can be republishing “Certain to Violence,” translated by Ralph Manheim. The reissue comes as contemporary consideration of Ouologuem’s work by readers and teachers is holding the outdated accusations as much as new mild: Ought to what Ouologuem did actually be thought-about plagiarism? Or had hasty criticism, maybe tinged with racism, destroyed one of many literary star of his technology?

There isn’t any query that Ouologuem copied, tailored and rewrote phrases, generally total paragraphs, from many sources.

The borrowings probably start with the novel’s opening sentence, “Our eyes drink the brightness of the solar and, overcome, marvel at their tears.” Critics have discovered it closely impressed by one other award-winning novel revealed years earlier, “The Final of the Simply,” which begins with, “Our eyes register the sunshine of useless stars.” Dozens of different similarities with “The Final of the Simply” fill the pages of “Certain to Violence.”

However what if, teachers are asking, these démarquages, as Ouologuem described the borrowings, have been an inventive approach — a kind of anthology that poured the canon of Western literature into an African context, or an assemblage or collage, like that utilized by visuals artists like Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso, however utilizing phrases?

“It’s not plagiarism, it’s one thing else,” stated Christopher L. Miller, an emeritus professor of African American Research and French at Yale College, who’s engaged on a compilation of borrowings within the ebook. “I don’t suppose we now have a phrase for what he did.”

Ouologuem was born in 1940, in central Mali, and moved to Paris when he was 20. He entered the celebrated École Normale Supérieure, because the poets and politicians Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal and Aimé Césaire of Martinique, each champions of the anticolonial Négritude motion in literature, had completed many years earlier.

He wrote at a frenzied tempo. At 23, he despatched his first manuscript to a writer, Éditions du Seuil; inside little greater than a yr, he despatched two extra. All have been rejected. “Certain to Violence” was his fourth try.

When the ebook was first revealed in France, critics heaped reward on Ouologuem, then 28 years outdated. Launched in the US in 1971, the ebook was referred to as a “skyscraper” by The New York Instances — a piece that deserved “many readings.”

The novel, composed of 4 elements, varies in fashion, drawing from West African oral custom, historic tales, theater and modern novels. It’s a searing exposé of the centuries of violence that passed off in elements of Africa, each earlier than and through European colonization.

From its first pages, “Certain to Violence” is uncooked and sarcastic: Telling the story of the fictional Saif dynasty, which the reader follows from the thirteenth via the twentieth centuries, would make for poor folklore, the narrator writes. As a substitute, readers encounter a world the place “violence rivals with horror.” Youngsters have their throats slit and pregnant ladies have their stomachs minimize open after they’re raped, below the helpless eyes of their husbands, who then kill themselves.

Sarr found “Certain to Violence” as an adolescent in Senegal, because of a professor who lent him an outdated copy with pages lacking. The ebook “sparkled,” Sarr stated, even because it shed a harsh mild on the continent, portrayed as rife with slavery, violence and eroticism.

“It’s an epic story of human cruelty set in Africa, similar to it might have occurred — and did — in the remainder of the world,” Sarr stated.

Even earlier than accusations of plagiarism surfaced, Ouologuem’s portrayal of Africa triggered outrage amongst African intellectuals. Amongst them have been towering figures like Senghor, who described the novel as “appalling.”

Ouologuem shrugged off the criticism of his friends. “It’s unlucky that African writers have written solely about folklore and legend,” he stated in a 1971 interview with The Instances.

The accusations of plagiarism got here shortly after the ebook’s publication in English. In 1972, an nameless article in The Instances of London’s Literary Complement pointed to a number of similarities between “Certain to Violence” and a novel by Graham Greene revealed in 1934, “It’s a Battlefield.”

Researchers and journalists noticed dozens of references and excerpts borrowed, plagiarized, rewritten — the suitable phrases to make use of are nonetheless up for debate — from sources as different because the Bible and The Thousand and One Nights, from James Baldwin to Man de Maupassant.

“What Ouologuem did was fabulous, however at occasions he was borderline, and even crossed that pink line,” stated Jean-Pierre Orban, a Belgian tutorial and author who studied Ouologuem’s correspondence along with his writer and interviewed his former Parisian classmates.

“He was infused with literature, quoting writers by coronary heart as if he was making their work his,” Orban stated. “He lived between actuality and fiction.”

A few of the first revelations of Ouologuem’s borrowing drew pushback from readers. When Eric Sellin, a distinguished professor of French and comparative literature, offered similarities between “Certain to Violence” and “The Final of the Simply” at a colloquium in Vermont in 1971, a younger attendant retorted, “Why are you white folks and Europeans at all times doing this to us? Every time we give you one thing good in Africa, you say that we couldn’t have completed it by ourselves.”

Additional analysis by Orban and others discovered that Ouologuem’s French publishing home, Le Seuil, was conscious of these similarities earlier than publication. However the criticism grew as Ouologuem vehemently denied any wrongdoing, claiming for example that he had despatched the unique manuscript with citation marks, an excuse that the majority discover doubtful.

“He was harm as a result of he had been misunderstood, and he had a virulent and reasonably clumsy perspective towards these assaults,” stated Sarr.

Lecturers and critics marvel if a Western creator would have confronted comparable criticism.

“I don’t suppose that in France, a European or French creator would have confronted the identical condemnation,” Orban stated. Borrowings, pastiches and literary methods have been usually thought-about a literary recreation, he argued. However it was one which Ouologuem wasn’t allowed to play.

Sarr believes {that a} white creator would have confronted an analogous backlash, however one that may have been restricted to the literary area — whereas Ouologuem, he stated, was castigated for who he was: an African creator plagiarizing Western canons.

Miller, the emeritus professor from Yale, means that Ouologuem flouted the principles on goal, not solely attacking the idea of Négritude by providing a radical revision of African historical past, but additionally the Parisian literary institution, in an act of inventive disobedience.

A bitter feud between Le Seuil and Ouologuem ensued, and the author moved again to Mali in 1978, based on his son. As soon as flamboyant and talkative, Ouologuem went practically silent upon his return, dedicating the remainder of his life to Islam.

“He was a wounded man, who got here again to curve up amongst his family members,” stated Ismaila Samba Traoré, a Malian author and journalist who interviewed Ouologuem within the Eighties.

His son, Ambibé Ouologuem, stated that his father had hung out at a psychiatric hospital in France earlier than shifting again to Mali. Upon his return, Ouologuem struggled to stroll, his son stated, and was cured with conventional strategies by his personal father.

The feud across the ebook and the bitterness that ensued additionally deeply impacted the remainder of the household: Ambibé Ouologuem stated he needed to go to highschool in secret, with the assistance of his grandmother, as a result of his father wished him to concentrate on learning the Quran.

“My father was happy with being African and Malian, and had at all times refused to use for French citizenship,” Ouologuem stated.

In Mali, Ouologuem’s ebook is taught in some excessive colleges, but it surely stays little recognized past mental circles even in West Africa. Mali’s authorities has vowed to create a literary award devoted to him, but it surely has but to be introduced. In accordance with his son and those that have studied him, it’s probably that the creator left unpublished manuscripts in Mali or in France.

To Sarr, the Ouologuem affair is a literary tragedy.

“I might be glad,” he stated, “If ‘Certain to Violence’ could possibly be stripped of its maleficent aura, its darkish legend. If we might learn Ouologuem once more and simply take into account his ebook for what it’s — an amazing novel.”